Chemical attack can happen to the glass lining, repair materials or steel.

Glass

Minimum available glass thickness:

While glass lining is well known for its exceptional corrosion resistance, you still need to take into account that it does corrode. The rate will normally be determined by the chemistry and temperatures involved in the process. Still, there is a diminishing of the glass thickness over time that needs to be taken into account and checked periodically. When glass thickness becomes excessively worn you may notice a number of symptoms like loss of fire polish, smoothness and even chipping and pinholes. Also, as we discussed in our post about how glass-lined vessels are made, the initial ground coat (roughly 0.015-0.025") is not as corrosion-resistant as the rest of the lining, so when the thickness gets below 0.030", there is usually not a lot of corrossion-resistant glass left. The only way to repair the depletion in the lining is to add a new one via reglassing.

Corrosion by water:

The alkaline ions that are found in distilled, hot water can actually leach onto the glass surface when they are in the vapor phase and lead to a roughening of the glass surface and possibly chipping. You may also find vertical ridges if the damage is caused by condensate running down the wall. The preventative solution is to clean the vessel with water that includes a small amount of acid. Once the damage has occurred, reglassing is necessary.

Corrosion by acids:

While glass provides excellent resistance to most acids, there are three types which cause significant damage – hydrofluoric acid, phosphoric acid, and phosphorus acids. When glass is attacked by these acids, especially when they are concentrated solutions, corrosion can occur quickly. Temperature also plays a key role in speeding up the contamination process.

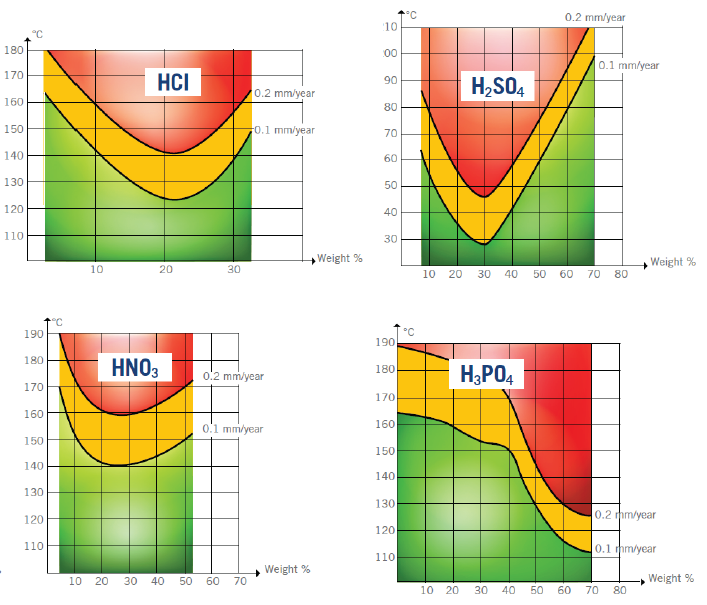

The following isocorrosion curves have been established to illustrate acid concentrations in relation to temperatures at which the weight losses correspond to 0.1 and 0.2 mm/year. The red area indicates where the use of glass is not advisable; yellow identifies that care must be taken of the advance of corrosion, and the green area advises that glass can be used without problems.

Corrosion by alkalis:

Hot and caustic alkalis should be avoided in glass-lined equipment. Silica, the main component of glass is very soluble in alkali solutions, making chemicals such as sodium hydroxide and potassium hydroxide a hazard to your equipment. (If you’re interested in looking at some more isocorrosion curves, you might want to download our Introductory Guide to Glass-Lined Steel Equipment.) If you have to add an alkali to your process, it should always be done so via a dip tube and the corrosion rate should be anticipated so you can plan when your vessel will require a reglass. Visual signs that your equipment has been corroded by alkalis include a dull, rough finish, pinholes, and chipping.

Corrosion by salts:

Salts corroding glass is based on the formation of acidic ions that attack the glass. The level of damage depends on the type of ion that forms. Acidic fluorides tend to be the most damage inducing. The best preventative measure is to anticipate the negative effects of these acid ions such as chlorides, lithium, magnesium and aluminum. When damage is caused from the liquid phase, there is a significant loss in fire polish and a roughening of the surface; in the vapor phase the attack is more concentrated to a specific area. Reglassing is the best solution for repairing this type of corrosion.

Repair Materials

Degradation of tantalum patches and plugs:

Tantalum is a commonly used repair material for glass because it has very similar corrosion resistance. There are, however, a few exceptions in which tantalum corrodes at a greater rate. In these instances, the tantalum may embrittle when hydrogen is the byproduct of a corrosive reaction. By avoiding galvanic couples, you can help deter this from happening. Regular inspection of all patches and plugs should also be performed to check for signs of embrittlement (these signs being missing pieces or cracks in the tantalum). Sometimes a small amount of platinum is applied to the plug to prevent embrittlement. In addition to cracking, glass fracture around the repair area and a rust-colored stain are also signs of damage. A damaged plug should be replaced, but if the same issue repeats itself, the solution is to come up with an alternative metal that can be substituted for the tantalum.

Attack of furan cements:

There are certain process environments that can attack furan cement. Strong oxidizers and sulfuric acid solutions and some moderately strong acids are typical culprits. There is often no visible sign that the cement has been affected. If you notice a gap between your repair plug and the glass surface, though, this is an indication that the cement has been compromised. In this instance, the repair should be redone and a different type of cement should be selected.

Attack of silicate cements:

Silicate cements, on the other hand, tend to be vulnerable to water or steam (when they are not completely cured), alkalis and hydrofluoric acid. As with other types of cements, the only indication of attack is usually a gap found in between the repair plug and glass surface and the solution is to repair the damaged area using another type of cement that is more compliant with your process.

Damage to PTFE components:

PTFE is a common material used in nozzle liners, agitator blade “boots”, repair gaskets, and other components. Acetic acid, polymerizations (e.g. PVC), and bromine are all examples of compounds that can permeate and degrade PTFE. Additionally, PTFE has a temperature limitation of 500°F and can develop HF vapors at higher temperatures that…well, we all know by now what hydrofluoric acid can do to glass! When PTFE is damaged it is apparent from the cracked, torn, and/or blistered appearance exhibited by the otherwise smooth surface. If your operation requirements don’t match the limitations of PTFE, the material needs to be replaced with a different polymer or a modified PTFE that can withstand more extreme applications.

Steel

Corrosion from external spills or wet insulation:

An external acid spill, like the one that’s occurred in the image above, is a primary example of the type of damage that can be caused by an external spill. Due to the popularity of chemicals entering from a top head nozzle and existing from a bottom head nozzle, these are common areas where fluid can be inadvertently spilled or leaked. This type of incident is particularly damaging to the vessel because the external spill/leak generate hydrogen atoms that diffuse through the steel all the way to the glass/steel interface. There they form hydrogen molecules and build-up until the bond between the glass and steel are disrupted. This damage, known as “spalling” is usually too large for a patch or plug and therefore requires reglassing. Unlike standard reglassing though, a pre-bake is required before the glassing procedure is performed to remove nascent hydrogen out of the steel; otherwise the hydrogen will continue to diffuse and cause even more damage.

Damage from chemical cleaning of jacket:

Jacket care and cleaning is an important topic that we covered in a previous post and is critical to keeping your reactor running efficiently. Eventually, heating or cooling media accumulates and leaves unwanted deposits in your jacket, making it necessary to clean it out. When the incorrect cleaning solutions are used, such as hydrochloric acid or other acid solutions, this can have a devastating impact on your reactor, similar to the spalling we just described. To avoid this, be sure to use dilute sodium hypochlorite solution or another neutral cleaner. Damage of this kind will take on the fish scale appearance representative of spalling. Reglassing with “pre-bake” is necessary to rid the steel substrate of any remaining hydrogen.

Flange face spalling:

One of the most common types of damage found in glass-lined equipment comes from corrosive chemicals that escape from flange connections. This "edge-chipping" as it can be know, is caused by chemicals that leak through the gasket and attack the outside edge around the flange, causing glass to flake away on the gasket surface and ruining the sealing surface. Flange face spalling is corrected through the use of an outside metal sleeve, outside PTFE sleeve or epoxy putty.